Culture Matters – A Study on Presence in an Interactive Movie

We conducted a cross cultural study to test the influences of different cultural backgrounds on the user’s presence experience in interacting with a distributed interactive movie. In addition we were interested in the effects of embodied interaction on presence. The influence of culture background is clear – Chinese participants perceived more presence than Dutch participants in all conditions. The results also show that interaction methods (direct touch against remote control) had no influence, while embodiment (robot against screen agent) had mixed effects on presence.

1 Introduction

The user’s character is believed to influence the user’s feeling of presence. The user’s cultural background is often mentioned as such a characteristic [1, 2]. A few cross-cultural presence studies are available [3], but none investigated the relationship between the user’s cultural background and presence directly. As Sas and O’Hare [4, p.527] pointed out, a “large amount of work has been carried out in the area of technological factors affecting presence. …Comparatively, the amount of studies trying to delineate the associated human factors determinant on presence is significantly less.” This influence of culture on presence is, at this point in time, more of a conjecture than a proven fact, and therefore we conducted an empirical study to investigate the relationship.

In absence of a clear definition of what cultural factors may influence presence, a good approach is to include participants from clearly different cultures. Using Dutch and Chinese participants in our study optimized cultural diversion. Hofstede [5] provides an empirical framework of culture by defining several dimensions of culture, such as power distance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, uncertainty avoidance and long/short-term orientation. China and the Netherlands differ substantially on all dimensions except uncertainty avoidance (see table 1 ). Power distance, for example, refers to the extend to which less powerful members expect and accept unequal power distribution within a culture. The Netherlands rank very low on this dimension, while China ranks very high.

| Dutch | Chinese | |

| Power Distance | 38L | 80H |

| Individualism | 80H | 20L |

| Masculinity | 14L | 50M |

| Uncertainty Avoidance | 53M | 60M |

| Long Term Orientation | 44M | 118H |

From an application point of view, China is currently one of the most promising economic opportunities. Its vast populace and large physical size alone mark it as a powerful global player. China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth of over seven percent indicates its steaming economic situation. Most Chinese already have access to a TV and the local TV manufacturers satisfy the domestic market. However, technology utilizing presence is not yet produced or consumed. Awareness of cultural differences in presence may help companies to create better products for the different markets.

At the same time, we were interested in distributed interactive media and their influences on the user’s feeling of presence. We have entered a new media era: passive television programs become interactive with the red button on your remote control [6]. Video games come with many different controlling interfaces such as dancing mats, EyeToy®; cameras, driving wheels and boxing GametraksTM [7]. The D-BOX®; OdysseeTM motion simulation system even introduces realistic motion experiences, which were originally designed for theme parks, into our living rooms [8]. In the vision of Ambient Intelligence [9], the next generation of people’s interactive media experience will not unfold only on a computer or television, or in a head set, but in the whole physical environment. The environments involve multiple devices that enable natural interactions and adapt to the users and their needs.

Formerly, distribution only revered to the distribution of data or computational processes in a network. Ambient intelligent environments build on this technology and extend it by distributing synchronized and interactive multimedia content on to multiple devices. Previous systems already employed distributed presentation to enhance the entertainment experience and thereby increasing the immersiveness of the content. Multichannel surround sound systems, for example, distribute sound all around the audience and hence provide a more realistic and natural sound experience. The ambient intelligence [9] concept goes beyond such sound distributions by distributing content through other channels in the user’s environment. Displays in the room may show video clips, lamps may change its color and brightness, robots may dance and sing, and couches may vibrate. The virtual space or the content, then, is no longer yielded in traditional audio and video materials by one TV set, but now expanded into the user’s surroundings covering more sensory modalities. The light color, robotic behavior and the couch vibration are parts of delivered content, conveying a virtual experience but with a direct physical embodiment. Ambient intelligence is therefore a distinct extension to classical virtual environments.

However, distributing interactive content to multiple devices would also increase the complexity of interaction. The environment together may become difficult to understand and to control. To ease the situation, embodied characters, such as eMuu [10] or Tony [11], may be used to give such an environment a concrete face. These characters have a physical embodiment and may present content through their behavior and interact with the user through speech and body language. They can even be used as input devices.

Moreover, the influence of embodiment on the user’s presence experience seems unclear. On the one hand, embodiment extends the distributed content from an on-screen virtual environment to a physical environment. The physical embodiment improves the content’s liveness and fidelity by stimulating more sensors of the user. This might result in an increased feeling of presence [12]. On the other hand, the physical embodiment may transfer more attention from the virtual environment to the physical environment. The physical embodiment may remind the user of its existence in this world and may break down the illusion of being there and hence would result in less feeling of presence [2]. The division of attention itself might also have such an effect.

To control interactive content, the user requires interaction devices. A physical embodiment would invite direct manipulation. A robot could, for example, ask the use to touch its shoulder to select an option. Interaction with a virtual on-screen character may favor the use of a remote control. Embodiment in interactive media can therefore not be studied without considering the interaction method. We therefore included two interaction methods in our study.

In this framework of interactive distributed media we defined the following three research questions:

- 1.

- What influence has the user’s cultural background on the users’ presence experience?

- 2.

- What influence does the embodiment of a virtual characters have on the users’ presence experience?

- 3.

- Would direct touching the presented content objects bring more presence than pressing buttons on remote controls?

2 Experiment

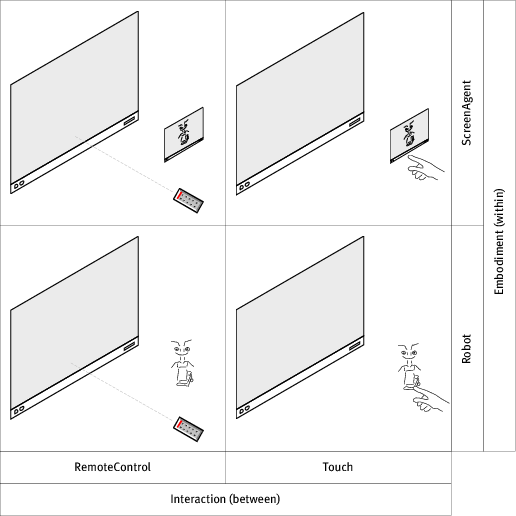

We conducted a 2 (Interaction) × 2 (Embodiment) × 2 (Culture) mixed between/within experiment (see figure 1 ). Interaction and culture were the between participant factors. Interaction had the conditions RemoteControl and DirectTouch, and culture had the conditions Dutch and Chinese. Embodiment was a within participant factor. Embodiment had the conditions ScreenAgent and Robot.

2.1 Measurements

The original ITC-SOPI [13] questionnaire was used and only the definition of the Displayed Environment in the introduction was adjusted to include the robot/screen character. The Chinese participants had a good understanding of the English language and therefore no validated translation was necessary for them. The questions remained unchanged and are clustered into four groups:

- 1.

- Spatial Presence, a feeling of being located in the virtual space;

- 2.

- Engagement, a sense of involvement with narrative unfolding within virtual space;

- 3.

- Ecological validity, a sense of the naturalness of the mediated content;

- 4.

- Negative effects, a measure of the adverse effects of prolonged exposure to the immersive content.

2.2 Participants

19 Chinese and 24 Dutch between the age of 16 and 48 (14 female, 29 male) participated in the experiment. Most of them were students and teachers from Eindhoven University of Technology, with various backgrounds in computer science, industrial design, electronic engineering, chemistry, mathematics and technology management. The Chinese participants were no longer than two years in the Netherlands. All participants had good command of the English language and were frequently exposed to English speaking media, such as movies, web pages, news papers and TV shows.

2.3 Setup

There computers are connected to the public network of Eindhoven University of Technology, with a bandwidth of 10Mb∕s, to serve three different actors. One laptop computer (Windows XP Professional, 1.4GHZ pentium CPU, 512MB DDR memory) was connected with a projector to serve a mpeg2 movie actor to a projected screen. The second computer has the same hardware configuration, but the operating system was Linux 2.6 (Fedora Core 2). Two actors were served from this computer: A physical robotic actor “Tony” through an infrared tower connected to the serial port; and an LIRC 1 actor that detects the input from a PlayStation 2 remote with an infrared sensor connected to another serial port. It also run the director that read the script, assigned the characters to the actors and scheduled the action tasks for the actors. The third computer (Windows XP, 1.4GHZ pentium CPU, 512MB DDR memory) connected to Philips DesXcape Smart Display through a firewalled local network to serve the virtual robot to a touch screen.

The experiment took place in a living room laboratory (see figure 2 ). The participants were seated on a couch in front of a table. The coach was 3.5m away from the main screen, which was projected onto a wall in front. The projection had a size of 2.5m × 1.88m with 1400 × 1050 pixels. The second screen was located 0.5m from the coach, standing on the table. The secondary screen was 30cm × 23cm with 1280 × 1024 pixels LCD touch screen ().

In the Robot conditions, the secondary touch screen was replaced with the Lego robot that had about the same height. In the ScreenAgent conditions, the secondary screen displayed a full screen agent of the robot.

The behavior of the screen based agent and the Lego robot were identical. They played the role of a TV companion by looking randomly at the user and the screen, but always looking at the user while speaking. Speakers were hidden under the table and were used to produce the speech, which was based on the standard Apple Speech Synthesis software. At the start of every movie, the character introduced himself and its role.

Since a media content that is acceptable in one culture can be perceived inappropriate, rude or offensive in another [14], the movie was designed to be culturally neutral. The movie had an international cast: the applicant was played by a Moroccan, the employer by a Dutch, the secretary by an American, and the passer-by by a Chilean. The actors spoke English. This study does not investigate the influence of media content on presence and therefore the story and movie cuts were neither too exciting nor too boring for both Dutch and Chinese participants. Otherwise they might have masked the effects of embodiment and culture.

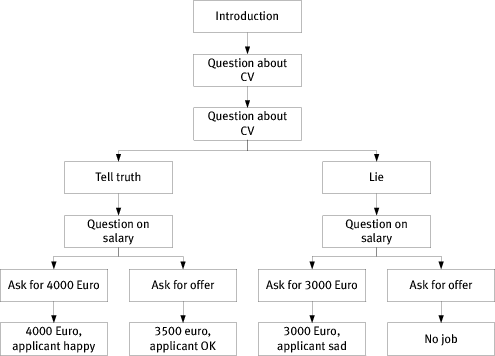

The interactive movie, about approximately 10 minutes, was about a job interview in which the participants had to make decisions for the applicant. The storyline was discussed with several Chinese and Dutch to assure that the actions of the characters would be plausible in both cultures. The movie had two decision points, which resulted in four possible movie endings (see figure 3 ). The participants chose different options for decisions almost all the time. At every decision point camera would zoom in on the applicant’s forehead (see figure 4 ). The actor then cycled through two options in his mind. He looked first to the left and thought aloud about one option, before he looked right and thought aloud about the second option. In the remote condition the screen would show one icon on the left and a different icon on the right. The icons were identical to two icons on the remote control. In the robot condition, the participant had to touch the left or the right shoulder of the robot to make the decision.

2.4 Procedure

After reading an introduction that explained the structure of the experiment the participants started with a training session. In this session, the participants watched an unrelated interactive movie that had only one decision point, during which the participants could make the decision using the remote control. Afterwards, they had the opportunity to ask questions about the process of the experiment. Next, the participant were randomly assigned to one of the between-participant conditions, which each consisted of two movies and a questionnaire after each movie. The participant received five Euros for their efforts.

3 Results

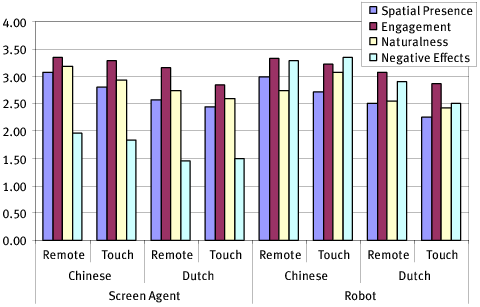

The mean scores for all measurements, including their standard deviations are presented in table 2 and graphically in figure 5 .

| Embodiment | Culture | Interaction | Measurement | Mean | Std.Dev. |

| ScreenAgent | Chinese | RemoteControl | Spatial Presence | 3.08 | 0.18 |

| Engagement | 3.35 | 0.37 | |||

| Naturalness | 3.17 | 0.32 | |||

| Negative Effects | 1.96 | 0.55 | |||

| DirectTouch | Spatial Presence | 2.79 | 0.37 | ||

| Engagement | 3.28 | 0.41 | |||

| Naturalness | 2.92 | 0.61 | |||

| Negative Effects | 1.83 | 0.52 | |||

| Dutch | RemoteControl | Spatial Presence | 2.56 | 0.29 | |

| Engagement | 3.17 | 0.51 | |||

| Naturalness | 2.75 | 0.50 | |||

| Negative Effects | 1.46 | 0.43 | |||

| DirectTouch | Spatial Presence | 2.44 | 0.45 | ||

| Engagement | 2.84 | 0.58 | |||

| Naturalness | 2.58 | 0.74 | |||

| Negative Effects | 1.5 | 0.36 | |||

| Robot | Chinese | RemoteControl | Spatial Presence | 2.99 | 0.2 |

| Engagement | 3.33 | 0.24 | |||

| Naturalness | 2.73 | 0.17 | |||

| Negative Effects | 3.28 | 0.42 | |||

| DirectTouch | Spatial Presence | 2.72 | 0.59 | ||

| Engagement | 3.22 | 0.43 | |||

| Naturalness | 3.08 | 0.32 | |||

| Negative Effects | 3.35 | 0.52 | |||

| Dutch | RemoteControl | Spatial Presence | 2.51 | 0.25 | |

| Engagement | 3.07 | 0.61 | |||

| Naturalness | 2.55 | 0.66 | |||

| Negative Effects | 2.9 | 0.4 | |||

| DirectTouch | Spatial Presence | 2.26 | 0.41 | ||

| Engagement | 2.86 | 0.56 | |||

| Naturalness | 2.42 | 0.59 | |||

| Negative Effects | 2.52 | 0.82 | |||

3.1 Embodiment, interaction and culture effect

A 2 (embodiment) × 2 (interaction) × 2 (culture) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. Interaction had no significant influence on any of the measurements. Embodiment and culture both had significant influence on almost all measurements (see table 3 ).

| Factor | Measurement | F (1,39) | p |

| Embodiment | Spatial Presence | 4.789 | 0.035 |

| Engagement | 0.515 | 0.477 | |

| Naturalness | 4.335 | 0.044 | |

| Negative Effects | 119.973 | 0.001 | |

| Culture | Spatial Presence | 19.49 | 0.001 |

| Engagement | 4.962 | 0.032 | |

| Naturalness | 7.494 | 0.009 | |

| Negative Effects | 24.491 | 0.001 | |

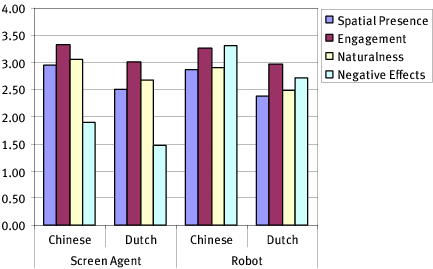

Interaction was removed as a factor from the further analyses since it had no effect on the measurements. The means for all remaining conditions are summarized in figure 6 and were used as the basis for the further analyses.

Paired Sample t-Tests were performed across both culture conditions. The measurements for Spatial Presence were significantly (t(42) = 2.235, p = 0.031) higher in the ScreenAgent condition than in the Robot condition. Negative Effects were significantly (t(42) = 2.38, p = 0.022) higher in the Robot condition than in the ScreenAgent condition.

Independent Samples t-Tests were performed. All measurements between the Dutch and the Chinese participants differed significantly, except for engage in the screen condition, which just missed the significance level (t(41) = 2.007, p = 0.051).

4 Discussion

4.1 Culture effects

The participants’ cultural background clearly influenced the measurements. Chinese participants perceived more presence than Dutch participants in all conditions.

The next question will be what aspects of the cultural background have the greatest influence on presence. Hofstede [15], Hofstede and Bond [16], Hofstede [5] suggested several dimensions through which cultures and organizations may be characterized. Peppas [17] points out that Chinese culture is much influenced by the 2000-year history of Confucianism, based on an intensive overview on the studies on Chinese culture. Confucianism, as a morel system, defines three cardinal guides (ruler guides subject, father guides son and husband guides wife) and five constant virtues (humanity, righteousness, propriety, wisdom and fidelity). It roots the Chinese culture has high power distance, low individualism, medium masculinity and uncertainty avoidance, and very much of long term orientation. Living in harmony, maintaining a good social network, and protecting one’s “face” are important in Chinese society.

Harmony (Hé, ) is the the key in Chinese culture, while in the west the key is finding ways to get things done, paying less attention to others. Harmony is also what traditional Chinese religions value. For instance, Chinese Taoism stresses “harmony with nature” () and Chinese Buddhism emphasizes “Harmony in six aspects” (Lìu Hé ):

- harmony in understanding reaches agreement (Jìan Hé Tóng Jǐe ),

- harmony in habits brings mutual improvement(Jìe Hé Tóng Zn ),

- harmony in physical conditions brings co-habitation (Shn Hé Tóng Zhù ),

- harmony in words avoids brawl (Yǔ Hé Wú Zhng) ),

- harmony in interests brings peace (Yì Hé Tóng Yùe ) and

- harmony in benefits brings co-existence (Lì Hé Tóng Jn ).

Even the word “monk” in Chinese (Héshang, ) preaches the idea of harmony.

This idea of harmony in the Chinese culture brings agreeableness into the blood of every Chinese person. Sacau, Laarni, Ravaja, and Hartmann [18] reports that agreeableness, one of the Big Five personality traits [19], is positively associated with Spatial Presence, which explains perfectly why the Chinese participants in our study perceived more Spatial Presence.

One might suspect that because of the idea of being harmony with other people and the importance of politeness and maintaining one’s or the other’s “face”, the Chinese participants might simply be more polite in answering questions. Our measurements show that they also gave higher scores to Negative Effects and therefore did not simply respond politely.

Comparing to Chinese, Dutch culture has much less power distance (means more equality and modest leadership), much higher individualism, more femininity, similar uncertainty avoidance and it is short term oriented. Maintaining the consensus (although it is often time consuming), and being (even pretending to be) modest are considered important in Dutch culture.

The Chinese and the westerners even see things differently [20] - the tend to look at the whole picture and rely on contextual information when making decisions and judgments about what they see, whereas the westerners tend to be analytical and pay more attention to the key, or focal, objects in a scene., for example, concentrating on the woman in the “mona Lisa” as opposed to the rocks and sky behind her. This would explain why Dutch participants get less engaged because the distributed presentations and interactions require the end users to consider the environment as a whole, paying attention not only to the main screen presentation (“mona Lisa”), but also to the context and the surroundings (the rocks and sky).

However none of Hofstede’s [1983, 1988, 1993] culture dimensions appear relevant to presence at first sight. One might speculate that the long-term orientation in Chinese culture would result in more patience towards imperfections. They might have more easily tolerated the noise emitted by the robot and the occasional visibility of a microphone in the movie. Further studies are necessary to investigate this issue.

4.2 Embodiment effects

The influence of embodiment on all measurements does not conform to the expected results defined in the construct of presence. According to Lessiter et al. [13],

Whilst in the current study Negative Effects was not strongly correlated (positively or negatively) with Engagement or Ecological Validity, it was significantly but modestly (and positively) related to Sense of Physical Space.

However, in our results Spatial Presence and Naturalness are higher in the ScreenAgent condition, while Negative Effects was higher in the Robot condition. Negative Effects appear to have been affected by something else than presence.

During the experiment, the robot’s motor emitted noise, which caused the participants to look at it. A moving physical object is potentially dangerous and hence attracts attention. Clearly, the robot emphasized the participants feeling of being in the room and not in the movie and thereby reducing the presence experience. The screen character did not emit noise and is unable to pose physical danger to the user. It therefore did not attract as much attention as the robot.

The participants were frequently switching between looking at the movie and the robot and hence divide their attention. This switching made it hard for the users to stay focused and might cause the high negative experience. Eggen, Feijs, Graaf, and Peters [21] showed that a divided attention space reduced the users immersion. Further research is necessary to determine if divided attention increases the negative effects of multiple displays. The extra costs necessary to build and maintain a robot for an interactive movie appear unjustified in relation to its benefit.

4.3 Effects of direct touching

The different interaction methods (using a remote control or touching directly) had no influence on the measurements. The participants did not experience more or less presence when they interacted with a remote control or with the screen/robot directly. This is to some degree surprising, since the participants had to lean forward to touch the screen/robot directly, while they could remain leaned back using the remote. The necessity to make a choice might have overshadowed the difference in physical movement. To create compelling sense of presence it might be useful to pay more attention to the physical output than to the input.

4.4 Future Research

In this study, several factors were investigated besides the cultural background of the participants. It might be beneficial to conduct a dedicated study on the influence of culture on presence. Such a study could then also cover more than the two cultures investigated in this study. In addition, it appears necessary to further connect the results of such a study to existing results in other research areas, such as cross-cultural communication studies. Qualitative interview might help to gain better insights into to social and cultural viewpoints of the participants in relation to presence.

Ambient Intelligence is currently a major research theme in the European academic and commercial world, but the results of this study show that cultural aspects do play a role in the design of future technology. Given China’s rapid grow and potential, it might be valuable to include an ”Eastern Perspective” into the European research, in particular since more and more consumer electronics are produced and consumed in Asia.

5 Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Loe Feijs, Maddy Jansen and Kees Overbeeke for their help and support. In addition, we would like to thank all participants of the study.

References

[1] W.A. IJsselsteijn, H.d. Ridder, J. Freeman, and S.E. Avons. Presence: concept, determinants, and measurement. Human Vision and Electronic Imaging V, 3959(1):520–529, 2000.

[2] J. Freeman, J. Lessiter, and W. IJsselsteijn. An introduction to presence: A sense of being there in a mediated environment. The Psychologist, 14:190–194, 2001.

[3] T.-T. Chang, X. Wang, and Lim. Cross-cultural communication, media and learning processes in asynchronous learning networks. In HICSS (the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences), pages 113–122, 2002.

[4] Corina Sas and Gregory M. P. O’Hare. Presence equation: an investigation into cognitive factors underlying presence. Presence: Teleoper. Virtual Environ., 12(5):523–537, 2003. ISSN 1054-7460. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/ 105474603322761315.

[5] Geert Hofstede. Cultural constraints in management theories. Academy of management executive, 7(1):81–94, 1993.

[6] J. Bennett. Red Button Revolution - Power to the People. 2004. URL http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/speeches/stories/bennett_mip.shtml.

[7] In2Games. Gametrak :: Come in and Play. 2005. In2Games Corporate and Press Site: http://www.in2games.uk.com.

[8] D-BOX. D-BOX Motion Simulators. 2005. D-BOX Technologies Inc. website: http://www.d-box.com.

[9] Emile Aarts and Stefano Marzano. The New Everyday View on Ambient Intelligence. Uitgeverij 010 Publishers, 2003.

[10] C. Bartneck. eMuu - An Embodied Emotional Character for the Ambient Intelligent Home. Phd thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, 2002.

[11] C. Bartneck and J. Hu. Rapid prototyping for interactive robots. In F. Groen, N. Amato, A. Bonarini, E. Yoshida, and B. Kröse, editors, The 8th Conference on Intelligent Autonomous Systems (IAS-8), pages 136–145, Amsterdam, 2004. IOS press.

[12] M. Lombart and T. Ditton. At the heart of it all: The concept of presence. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 3(2), 1997.

[13] J. Lessiter, J. Freeman, E. Keogh, and J. Davidoff. A cross-media presence questionnaire: The itc sense of presence inventory. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 10(3):282–297, 2001.

[14] M. Lu and D.F. Walker. Do they look at educational multimedia differently than we do? a study of software evaluation in taiwan and the united states. International Journal of Instructional Media, 26(1), 1999.

[15] Geert Hofstede. The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 14(2, Special Issue on Cross-Cultural Management):75–89, 1983.

[16] Geert Hofstede and Michael Harries Bond. The confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4):4–21, 1988.

[17] Spero C Peppas. Us core values: a chinese perspective. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 24(6):58–75, 2004.

[18] Ana Sacau, Jari Laarni, Niklas Ravaja, and Tilo Hartmann. The impact of personality factors on the experience of spatial presence. In Mel Slater, editor, The 8th International Workshop on Presence (Presence 2005), pages 143–151, London, 2005. International Society for Presence Research, University College London. ISBN 0-9551232-0-8.

[19] R. R. McCrae and O. P. John. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2):175–215, 1992.

[20] Hannah Faye Chua, Julie E. Boland, and Richard E. Nisbett. From The Cover: Cultural variation in eye movements during scene perception. PNAS, 102 (35):12629–12633, 2005. URL http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/102/35/12629.

[21] B. Eggen, L. Feijs, M.d. Graaf, and P. Peters. Breaking the flow - intervention in computer game play through physical and on-screen interaction. In the ’Level Up’ Digital Games Research Conference, 2003.